- Home

- Sharell Cook

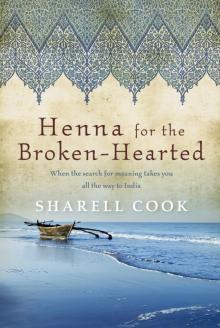

Henna for the Broken Hearted Page 4

Henna for the Broken Hearted Read online

Page 4

The conversation left me filled with wonder at the world and how two completely different, and in fact opposite, cultures existed on the same planet. It was a feeling that would remain with me as I continued to discover extreme differences between the cultures.

Western facilities were conspicuously absent at the women's centre. That afternoon I had my first encounter with the infamous Indian squat toilet. There it was, beckoning me, a porcelain basin in the floor, with a hole and space for my feet on either side. I soon discovered there are two challenges involved in using the squat toilet – aim, and the cleaning of body parts afterwards. Making a stream of urine go down a porcelain hole without splashing or spraying the sides and getting wet feet is no easy matter. And even if it is achieved, the task of cleaning the nether regions still remains.

Foolishly, I didn't carry any toilet paper. Cleaning would have to involve my left hand, the small mug nearby, and water. But with my bottom pointing downwards, and loose salwaar kameez pants bunched around my ankles, how would it be possible to pour the water onto myself without getting everything wet? I managed to splash the water around in a totally unsatisfactory manner, and had the displeasure of it dripping down my legs and on to my clothes as I stood up. A large bucketful of water was waiting by the side of the door, so I quickly tipped it down the toilet to flush it and beat a hasty retreat.

By the end of the day, I was exhausted and couldn't wait to go home. I dragged my weary body onto the packed bus and wedged myself in between the other commuters who were standing.

The one redeeming feature of the buses is their ladies only seating. While it really highlights the distinction between men and women in India, and how they interact, it also helps prevent any untoward incidents between the sexes. Unfortunately, during peak hour there's barely any room to move, let alone sit, on the bus. A portly Indian male's potbelly pressed into my back. No sooner had I managed to disengage myself from it than I felt a hand on my bottom. Its owner whispered something unintelligible to me as he squeezed past. I promptly rewarded him with a swift and strong elbow for his effort. The most disconcerting thing was that he looked so respectable, like a decent family man.

It was a relief to wash the day's sweat and grime from my body. Somehow, I managed to summon my last remaining bit of energy to go to the apartment next door to reheat the curry and rice dinner that Kali had kept in the fridge for me. Then I promptly crawled into bed and fell into a deep sleep under my bright purple mosquito net.

As the week progressed, people at work seemed to become more open to my presence, and warmed to me more. I warmed to them too and was keen to befriend them. On the plus side, I always had company in the showroom. It was Nalini's job to oversee it. A very attractive Bengali woman, she was slight in build with sharp features, sparkly eyes and an engaging smile. We were often joined by the women who attended the centre. They would sit in the corner and stitch their handicrafts.

‘Do you know any Hindi? Bangla (Bengali)?’ they eagerly inquired.

‘Aap kaise hain? (How are you?)’ I offered. It was one of only a few things I knew how to say in Hindi. But it was enough to please them. They were even more amused when I pulled out my Hindi and Bengali phrasebook and attempted to read from it.

‘Aa-mi Bang-la bohl-te paa-ri-nai (I can't speak Bengali),’ I stumbled and they laughed. It soon became apparent that my phrasebook would be the thing that united us.

‘Read, we will help,’ they encouraged me.

I quickly grew very fond of two women in particular – an irrepressible girl named Lakhi, and a gentle older Muslim woman called Mastari Begum.

Lakhi taught me how to reprimand people in Bengali. Baloh naa. (Not good.) Aap ni karap. (You are bad.) Aap ni dushtu. (You are naughty.) Mastari, who didn't know much English, would just sit next to me and smile. When English was spoken, it was mostly broken Indian English, as the women hadn't been formally educated in the language.

It wasn't long before I got to see firsthand the impact the women's centre had on people's lives. Two volunteers from another organisation brought a mother and her young daughter to the centre one afternoon. They were extremely poor, distraught and dejected-looking. The daughter was still at school, but had already developed some skills in making handicrafts. The mother begged for advice and assistance for her daughter. After sitting down and talking to Meera in the office, the mother left, crying tears of happiness, knowing there could be a positive future for her daughter after she finished school.

‘Phir milenge (We'll meet again),’ I tried to reassure the mother as she left, in the only other Hindi phrase I knew. She reached out, grabbed my hand and kissed it. I felt like crying myself, it was so emotional. However, that I was almost moved to tears by her plight indicated that I wasn't really suited to a career in social work. I had actually given serious thought to it when pondering my future. Yet, the reality was that I didn't have the tough mind needed to deal with confronting situations and other people's suffering. I was sensitive and easily saddened. I wished I could wave a magic wand over her and take away all her problems. But life isn't like that.

Just seeing the depth of the mother's despair reminded me of how many positives I still had, and took for granted, in my existence. It left me feeling disturbed for the rest of the afternoon. My sombre mood didn't go unnoticed.

‘Come, sit, drink tea,’ the other women tried to make me feel better. Little did they know that I had had enough of sitting on the floor all day, and had had enough tea (try explaining to Indians that you don't want tea, and they'll look at you incredulously).

I was thankful it was already dark when I took the bus home that night. The dim glow of the lights took away some of the harshness of reality and gave the streets a magical feel. I leaned my face towards the open window and breathed in the sights and smells – the dust, the smog, the spices, the incense. Street vendors lined the pavements. Everywhere, people. The foreignness of my surroundings made me feel like I was a very small part of a huge, unfathomable picture. It was strangely reassuring.

Before long, it was Christmas Eve. Kolkata has a nostalgic relationship with Christmas, as a result of its colonial history. Tara, Claudine and I decided to go shopping in the heart of Kolkata. The taxi dropped us at the iconic stretch of Park Street near Chowringhee Road, at the opposite end to where the street connects with Park Circus. The city's most prestigious thoroughfare, it was named after a deer park that existed there in the late eighteenth century, during the glory days when Calcutta was the capital of British India. With those days long gone, and with Calcutta metamorphosing into Kolkata, the street has now been renamed Mother Teresa Sarani after the Albanian nun who dedicated herself to helping the poor.

It's clearly still a prestigious part of town, even if it doesn't glitter like it used to. There was a time when Park Street was the focal point of the whole city, if not the country. The street's grand old mansions housed the finest of shops and restaurants on their ground floors, and the richest of the rich in airy apartments on the upper floors. India's first independent nightclub opened there, with soulful voices and swinging six-piece bands, along with India's first department store.

Today, the main symbol of Park Street's pre-eminence is The Park Hotel. Restaurants are still filled to capacity but the class of diners has changed, and dinner jackets are no longer compulsory. DJs have replaced the live jazz and cabaret, and shops selling pirated books and fake perfume have encroached where once they wouldn't have dared.

Around the corner Chowringhee Road has been renamed Jawaharlal Nehru Road. It's now dominated by packs of pavement vendors selling cheap jewellery, western and Indian clothes and handbags. We tried to browse as we walked, but the clamour and commotion didn't make it a peaceful activity.

A bangle seller latched onto me.

‘Madam, just looking. I show you. See, pretty bangles. Very cheap,’ he assured me.

I made the mistake of smiling at him and pausing to take a peek. They didn't interest me, and I att

empted to move away.

‘No madam, I give you good price. How much you want to pay?’ he persisted.

‘Really, I don't want them,’ I replied.

‘But madam, best deal,’ he beseeched.

I turned away and began to push through the crowd to catch up with the other girls, who were already well ahead.

He followed me. ‘Madam! Madam! Wait!’

Some people find it easy to be abrupt and dismissive of these kinds of annoyances. I don't. I never want to seem rude and always find the attention hard to ignore, no matter how irritating. All of a sudden, I remembered why India can be so tiring.

The bangle seller was still pestering me by the time I reached the girls.

‘Looks like you've got yourself a fan,’ they laughed.

‘I can't get rid of him,’ I sighed.

At that point, I was feeling really hungry and dragged the girls into a nearby restaurant to eat.

‘I'd have to be paid to eat here,’ Claudine complained as I ordered my aloo gobi (potato and cauliflower curry). It was a dingy dining establishment, where functionality took priority over aesthetics and tasteful decorations were conspicuously absent. Yet, when the aloo gobi arrived, it was undeniably good. And it cost only 15 rupees (45 cents). Claudine helped herself.

‘You really don't look like you're 31,’ she said again as I got my bag to leave. ‘But I can see that you act like a grown-up and have nice things like one.’

I was amused and alarmed. How were 31-year-olds expected to act? Did 31 really seem that old? And when had it stopped seeming old to me? I'd been happy to turn 30. I still felt and looked young, but was glad for the wisdom that I'd acquired during my twenties.

‘You know,’ she continued, ‘I think the reason why you get hassled so much here is that you're smiling all the time. Every time I see you, you're smiling.’

No doubt she was right. Smiling came naturally to me. But it also disarmed people, and encouraged them to be persistent. Claudine, on the other hand, had her own way of dealing with unwanted attention. She waved, said ‘See you later’, and walked away without looking back. It was a non-offensive but effective technique that even amused many Indian onlookers. I'd seen them start laughing at their counterparts after witnessing it.

For the next few hours, we immersed ourselves in Kolkata's historic bargain shoppers' paradise of New Market. Another remnant of the British Raj, it sprawls over a series of buildings and the surrounding area on Lindsay Street. It had been established solely as a white man's market, providing exclusive goods to the affluent English populace. These days, locals claim there's nothing its 2500 stalls don't sell. We wandered through the warren of corridors, trying on Indian clothes in infinite shades and designs until we were exhausted. Afterwards, we headed to Peter Cat restaurant to replenish ourselves.

Opened in the swinging 1960s, Peter Cat had managed to survive the passage of time and remained as popular as it was back in its heyday. The dimly lit interior spoke of history. The waiters were resplendent in crisp Rajasthani white and red costumes, which matched the colours of the restaurant's interior but curiously contrasted with its name – a name that didn't give away much at all. However, a bit of research revealed that it's the namesake of a famous cat who lived in Lord's cricket ground in London from 1952 to 1964 (and Kolkata is a city obsessed with cricket).

I ordered a Tom Collins. Priced at only 74 rupees ($2), it was the cheapest cocktail I'd ever had, and was likely to ever get in India. Already drained by the day's activities, I struggled to stay awake after drinking it.

The Christmas lights twinkled warmly on Park Street as we climbed into a taxi to go home. Nevertheless, by the time we arrived back at the apartment building, melancholia had descended over me like the mist that falls over Kolkata night after night in winter. Kolkata's winter lacks the bitter coldness, cloudy skies and rain of the Melbourne winter. However, it's extremely dusty and the chill of the night air adds impenetrable thick mist and fog. Not only does it make it very difficult to breathe, it often grounds flights as well. My head pounded from the noxious blend.

Since childhood, Christmas Eve has been a magical occasion filled with anticipation for the day to follow. This Christmas just wasn't going to be the same. Music from a Christmas Eve party being hosted for residents in the apartment courtyard drifted through my apartment windows. But I couldn't summon enough interest to investigate.

Christmas day dawned bright and sunny, but with the usual layer of Kolkata smog. It was Christmas morning in India but it was already Christmas afternoon in Australia, where celebrations would be in full swing, eating and drinking at a relative's house. It seemed so far away, a detached and distant land. For me, Christmas morning had involved the same ritual since childhood – sitting on the floor and unwrapping presents with my parents. I had never spent a Christmas away from my family until now.

Just last Christmas, Michael was still in my life. We had the presents ritual as usual but he had later spent a lot of time out of sight on the phone, when we were at his father and stepmother's house for Christmas lunch. Looking back now, it was a sign. But although I noticed it at the time, in my ignorance I didn't really think anything of it. My, how so much can change in a year! If anyone had suggested to me that I would be spending Christmas in India, on the brink of divorce this year, I would have thought it totally obscene. Yet, here I was.

Claudine, Tara, Georgie, Nicole and I decided to go to the Christmas-lunch buffet at the luxurious ITC Sheraton hotel in our Indian clothes. We wanted to give our appearance an Indian touch, but looked forward to eating something other than curry. I'm blessed with a very strong stomach and hadn't experienced any digestive problems at all, but some of the other girls weren't so fortunate.

At 1200 rupees ($30) per head, the buffet was affordable only to well-off Indians. The cost, which we regarded as quite a bargain for a sumptuous all-you-can-eat lunch with alcohol, was more than a week's wages for much of India's population. What we were entitled to as the middle class in our developed nations and were casual about was reserved for the privileged in India. I couldn't help noticing the distinction between us and the other portly Indian guests. Us, dressed in the cheap outfits we'd thrown together, and them resplendent in the finest of saris. Us, acting exuberant and unfussy; them, reserved but demanding. Us, with our bodies kept deliberately slim; them, displaying the desired roundness that comes from having more than enough to eat.

The disparity between rich and poor in India stretched deeper than that. The richest ten per cent of India's population owns over half the country's wealth, while the poorest ten per cent owns a mere 0.2% of it. Most of India's poor struggle each day just to make ends meet. Only yesterday, we had been alongside those people. Today, we were alongside the rich, playing the role of privileged tourists. The extremes seemed hard to justify.

Champagne flowed, a live band sang Christmas songs and a roving Santa stopped by our table to give us gifts and wish us Merry Christmas. His starkly white beard stood out against the deep coffee colour of his skin. It was Christmas, Indian style!

At the buffet, we had to search for roast meat among the dominating curries. I ate a plateful of curry because it looked so appealing. The roast turkey delivered to us by the chef next was delicious. And the desserts, laden with chocolate, were among the best I'd ever had.

After spending almost four hours in the dining room, we retired to an outdoor pavilion in the hotel's grounds. We reclined on the couches and admired the large marble bowls filled with colourful floating flowers, as fountains cascaded around us.

Outside the sanctuary of the hotel, the illusion was shattered and we were quickly reminded of exactly where we were. A short distance down the road, our taxi driver pulled over as a random Indian guy came running up alongside us. It seemed that he was a friend of the taxi driver and desperately wanted a lift. Despite the decrepit taxi barely accommodating the five of us, as well as the driver, he insisted on getting in the front with Claudine.

>

It was one of those mad Indian moments that we were completely unaccustomed to, and had no idea how to react. Vehicles are commonly burdened beyond their capacity: motorbikes carry whole families on them, with children gripping the handlebars in front of their father and sitting on their mother's lap. Any available space is used. The taxi lurched forward, with all of us aboard and the two Indian occupants clearly amused by the unexpected situation they'd found themselves in. It was probably the first time they'd been crammed in a car with a bunch of hyperactive white girls. The brakes were slammed on multiple times by the distracted driver, who had a few near misses as we shrieked in unison.

The day spent with the girls did wonders for my mood. They were young, innocent and carefree, and they made me feel that way too. Bonding with them gave me a huge boost.

‘You always seem so positive and happy,’ the girls said during the day.

This was a welcome revelation. I was relieved to know that, apart from the fact that I was noticeably underweight, the difficult year hadn't had an obvious impact on me. And, perhaps, I was more likeable than I thought.

Two days later, on what I thought was going to be an uneventful day, I arrived back at the apartment after work to find that my flatmate had moved in. My clothes and belongings had been picked up off the other bed in my room, which was acting as my wardrobe in the continued absence of any furniture, and unceremoniously dumped onto mine. Not long after, the door opened and a mature-looking Indian lady entered.

‘Hi, I'm Panna,’ she introduced herself in a British accent. She must have noticed the less than enthusiastic look on my face because she quickly added, ‘I didn't do that, by the way. It was Kali.’

Henna for the Broken Hearted

Henna for the Broken Hearted