- Home

- Sharell Cook

Henna for the Broken Hearted Page 3

Henna for the Broken Hearted Read online

Page 3

‘He must be helping himself to the liquor while serving drinks,’ Sucharita declared in disgust after he'd departed.

After dinner, Sucharita delivered Tara and me to our accommodation. Again, I was surprised. We would be staying at Hiland Park; by Indian standards, a luxurious new high-rise residential complex on the outskirts of town. It was the first high-rise development in Kolkata, and its gleaming white towers rose starkly from the vacant grassy surroundings. The complex contained nine towers in total, ranging in height from 17 to 28 floors. Within it were an astonishing 941 apartments. We were on the fifth floor of one of the shortest towers.

It soon became obvious that my accommodation wasn't ready. The apartment that my room was located in was unoccupied and mostly unfurnished. This was in contrast to the other volunteers, who were sharing a comfortably lived-in apartment down the hall. While my apartment had a couple of beds, couches still in their plastic wrapper, a coffee table and a fridge, there were no kitchen cupboards, no curtains, no wardrobe, no mosquito nets, no washing machine, no microwave, no cooking utensils and no hot water.

‘You'll have to adapt,’ Sucharita told me, adding that I'd be getting a flatmate and more furniture soon. I learned pretty quickly that though congenial on the surface, she was prone to emotional outbursts when volunteers failed to adapt as required. It also became apparent that ‘adapt’ was the most favoured word in her vocabulary.

In that empty apartment in an unfamiliar city that night, I was assailed by packs of massive and unrelenting mosquitoes as I tried to sleep. My loneliness was oddly offset by my gratitude at the opportunity to be alone for a while.

The next morning I drifted around the apartment, examining its whitewashed walls and marble floors and benches. On the floor in a corner of the other bedroom I found a small bronze statue of Lord Ganesh, a box of incense, incense holder and matches. I gently carried them to the coffee table in the living room and lit the incense. Its soothing, ancient smell instantly calmed and cheered me. Although it had only been a night since I'd arrived in Kolkata, I thought that I might actually be okay there.

It wasn't long before Sucharita arrived at the apartment. I had only the one day to settle in before starting work at the centre for underprivileged women that I'd been assigned to. She was keen to start the orientation process. Behind her was a small dark man.

‘This is Kali,’ she introduced him. ‘Kali will be providing your food and cleaning the apartment.’

It was a curious name, one better known as the fearsome Hindu mother of death and Kolkata's presiding deity. With blood-drenched tongue jutting out of her black face, hands bearing bladed weapons, and ears and neck decorated with dismembered body parts, the true Kali is a terrifying sight. The name also means ‘black one’.

It was obvious that Kali, the servant, was uneducated and couldn't speak much English. Communication would be interesting. He went about his work while Sucharita took me to the other apartment to meet the rest of the volunteers. They were all in their late teens and early twenties.

‘You can't be!’ they exclaimed, when I told them I was 31. ‘You only look like you're 25.’ Unconfident and unsure of myself, I certainly felt that young.

The youngest two girls, Georgie and Nicole, were also from Australia, on their first trip overseas. They were suffering from severe culture shock and couldn't engage with India's confronting personality and were keen to leave. Bubbly, blonde Claudine from England appeared to have settled in well. Cliona, who was from Ireland, was out, but I was told she had been there the longest and had apparently become almost Indian. She could speak Hindi, often wore Indian clothes and had made plenty of local friends.

It emerged that the girls were all volunteering together, teaching in schools and slums; I would be the only one working at the women's centre. Not only did I have to live by myself, I had to work by myself too.

I felt even more anxious when Sucharita told me I would have to take the bus to work. The journey would take an hour each way, and I'd have to change buses. I was in an unfamiliar city and I didn't speak the language. How would I ever cope?

‘We will take a practice run,’ Sucharita said. ‘And on the way, we'll go to a shopping centre so you can buy some Indian clothes. You must wear Indian clothes to work to blend in with the women there as much as possible. They are poor and will feel more comfortable if you dress like them.’

This was getting harder by the minute. Sure, they might feel comfortable, but what about me? I'd wanted to be a bit less concerned about my appearance in India but I could see that it wouldn't be possible if I had to dress in a certain, and completely untried, way. I would be more unsure of myself than ever.

The bus stop was located on the main road, a five-minute walk from my apartment. Heaving, rusty, mechanical monsters that belched out pollution ground to a halt there at irregular intervals. Hordes of people scrambled to get on and off before the conductor bashed the side of the bus with his hand and shouted something incoherent to let the driver know he should proceed.

‘We will take the number 1B to Dhakuria, okay?’ Sucharita instructed. ‘I want you to tell the conductor where we're going. It's important that you pronounce the name right and be understood.’

Our destination, which required a series of tongue acrobatics completely foreign to an English speaker, did nothing to put me at ease. The ‘dha’ is known as an aspirated, retroflex consonant. There's no equivalent to its pronunciation in the English language. The speaker has to touch her tongue to the roof of her mouth and flip it down, while breathing out and trying not to choke. The word ‘Dhakuria’ also requires a slightly trilled rolling of the ‘r’. I was being thrown in at the deep end.

Inside the bus, I squeezed myself onto a cramped wooden bench seat and awaited my fate. Most of the passengers were men, neatly dressed in the customary pants and shirts. The few woman sat segregated, with their saris wrapped immaculately around themselves and the pallu (loose end of the sari) often draped over their heads. Their long dark hair was scraped back into tightly woven buns and their faces were devoid of make-up. The warm shades of their skin blended together but contrasted against mine. Combined with my western dress, I stood out like a beacon. Despite the teeming humanity, I was isolated because of my difference.

It wasn't long before the conductor stopped in front of me. No matter how much I tried, my tongue refused to position itself as needed. As all heads turned in my direction, the source of the shambling sound, I wished I was anywhere else but there. What had I gotten myself into? Whatever was I thinking coming to India by myself? I wasn't brave enough for this!

After my third hopeless attempt, Sucharita realised I wasn't going to make myself understandable and intervened. I resisted the urge to leap off the bus and run to the safety of my apartment. In this unfamiliar city that contained the population of Australia, I felt very much an outsider. I had no one to share my trials and tribulations with, empathise over the challenges or laugh over the misfortunes. I was going to have to rely on myself. I badly wanted someone to hold my hand.

As the bus crunched and groaned along, I distracted myself by looking out the window while the people of India played their lives out on the streets. So used to the quiet streets of Melbourne, it seemed like the whole of Kolkata was gathered by the roadside. Vegetable vendors sat hunkered down, their bright array of produce laid out on the ground in front of them for finicky Indian housewives to pick over. I'd never seen such varieties of gourds before. Men gathered around makeshift chai (tea) stalls, fashioned out of chunky bits of bamboo tied together. The richer shopkeepers were holed up in their small tin shacks, draped in assorted potato-chip packets and other consumable items. Cycle rickshaw walas rested, leaning up against their rickshaws, waiting for the next fare. People coughed and spat. Vehicles honked.

Around forty minutes later we reached Dhakuria. I took note that we disembarked next to a petrol station, and hoped I'd recognise it the next day.

‘From here, we'll take b

us number 45 to Park Circus,’ Sucharita told me. It wasn't long before the required bus lumbered up to us and we were on our way again. I found some comfort in the fact that Park Circus, a name reminiscent of the British Raj, didn't present with any pronunciation challenges.

Park Circus, I soon discovered, was aptly named. A huge roundabout with roads running off it in all directions, it had cars, buses, auto rickshaws, bicycles and a man carrying a heavy hessian bag on his head jostling for their place. Sucharita took me along Park Street, then down a side street to the women's centre where I'd be working. The centre was located on the top floor of a decaying, whitewashed residential building. The doorway was so low I had to bend down to enter. Inside, I met the people who ran the centre – Aarti, Meera and Nalini.

‘So, what do you do?’ they asked me.

‘I'm an accountant,’ I reluctantly replied.

‘Ah, perfect, you can work in the showroom,’ they decided. ‘A stocktake is needed.’

Inwardly, I groaned. A stocktake! I'd come all the way to India to get away from accounting, and I was going to have to do a stocktake. The universe has a sense of humour sometimes.

My hours were to be 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday to Friday, just like an office job. I knew the other volunteers were only working around five hours a day at their projects. It seemed unfair. However, the position would only be for five weeks, and I still hoped that I'd get to meet and work with the women who the centre supported.

While stopping to change buses at Dhakuria on the way back, Sucharita took me to the Dakshinapan Shopping Centre for my Indian wardrobe. This open-air shopping complex houses a number of handicraft emporiums, as well as row upon row of cheap, nondescript clothing shops. The task was to find a salwaar kameez or two that suited me. Every shopkeeper vied for my attention as soon as they saw me.

‘Madam, madam. Come look my shop. Yes, madam, can I help you?’

After being shown dozens of outfits, I finally found a red-and-brown patterned salwaar kameez for 150 rupees ($5), and another in blue for 250 rupees ($8). The salwaar kameez, a loose-fitting pants and tunic combination with dupatta (scarf), hung like a tent on my thin body. But it would suffice.

Back at the apartment, I knew I was going to have to do something about the mosquito menace. Although Hiland Park was located in the middle of nowhere, on a road known as the EM Bypass, it wasn't completely isolated. There was a shopping mall right in front of it. And, in that shopping mall was the closest thing I was to find to a western department store, the Big Bazaar.

To the uninitiated, the Big Bazaar is India's version of a discount department store. It's a two-storey mecca that stocks everything from food to fridges, to cookware to clothes. With a slogan of ‘Is se sasta aur accha kahin nahi! (nowhere cheaper or better than this!)’, it's been expanding through India and fuelling frenzies among shoppers at an alarming rate. No doubt, a sign of an emerging middle class with a disposable income.

That night marked the beginning of my strong love/hate relationship with the Big Bazaar. Blissfully ignorant, I was unaware that the colossal crowd milling around outside was also an indication of what was within. As I passed through a security check to be admitted indoors, the first thing that struck me was the complete disarray. Merchandise was clustered together in islands, piled onto tables and overflowing from large bins. Whole families hunted for bargains in huge groups, eagerly pushing past me in their hurry to unearth the next good deal. Trolleys acted as obstacles in already jammed thoroughfares.

All of this, I was later to learn, was no design flaw but purposely laid out that way. A neat and empty shop, which may appeal to foreigners like me, will never attract the masses in India. For Indians, shopping is entertainment. They like to be able to bump into people, chat, gossip and eat while shopping. The Big Bazaar, with its organised chaos, purposely facilitates this.

It certainly didn't make easy my mission of acquiring a mosquito net. My confusion only increased as I left the store. At the checkout, the mosquito net was placed into a plastic carry bag, which was then heat-sealed shut. At the exit, a security officer demanded to see my receipt, which was then hole-punched and returned to me. Neither process made sense, especially as it wasn't possible to check the contents of my sealed shopping bag against the items listed on the receipt. It would be a long time before I futilely stopped looking for logic in India!

The next morning, I managed to make my way to work and arrived on time. I was proud of the fact that I'd done it without any hiccups, or having to ask for help. I nervously stepped inside the building and, deciphering a handwritten sign instructing ‘Please Open Your Shoes Down’, removed my sandals.

Every day the women's centre opened with meditation and yoga, followed by music, singing and prayer.

‘Saab ka mangal, saab ka mangal, saab ka mangal, hoi re (Let good happen to everyone).’ It was touching and inspiring. Most importantly, for all the women from diverse backgrounds who attended the centre, it fostered hope and oneness. It was impossible to know, just by looking at the women, that they had suffered intense hardship and oppression, living in unhygienic conditions with the burden of having to meet the domestic and financial needs of their families. They were so composed and attractively dressed, although they looked at me with wary eyes.

Introductions were made over steaming hot cups of spicy chai. I felt as shy as the women, and didn't know what to say to them to bridge the divide between us. The women at the centre were taught skills that would empower them to earn a decent income and live a more dignified life. They learned how to read and write, make handicrafts, pickles and jam, market the goods and manage a small business. The showroom was a retail outlet for what they produced. It was stacked from floor to ceiling with eye-catching batik wall hangings, bedding, clothes, bags, aprons, greeting cards, leather purses and notebook covers. All of a sudden, the thought of immersing myself in their work and having to do a stocktake didn't seem so bad.

At lunchtime, Nalini and Meera invited me to join them in their office.

‘Come, sit,’ they directed me as they unfurled mats on the floor. I contorted myself into a cross-legged pose and positioned my lunch in front of me. It was a simple meal of rice and potatoes, cooked by some of the women at the centre. It suited me, as I'd always liked Indian food and had never had a problem eating it. Fortunately, I was given a spoon, and so was saved from having to make a clumsy attempt to eat with my fingers. But I would learn and become familiar with eating with my fingers by the time I left the centre. The trick is to use the fingers to work the food into a ball. Then with four fingers acting like a spoon, gather it up onto the fingertips with the thumb, place the thumb behind it, and lever it into the mouth.

‘So, tell us about yourself,’ they asked. Used to living communally, Indians like to know as much as possible about each other. There is little concept of privacy, so prized in the west. ‘How old are you and do you have a husband?’

Just the questions I didn't want to answer! I knew if I told them my true age but said I was single, they would think it strange since anyone over the ripe old age of 29 is looked on as being past marriageable age in India. I decided to be truthful but to say as little as possible.

‘Um, I'm 31 and yes, I do.’

‘How long have you been married? What is his work? He didn't mind you coming here?’

The questions kept coming. I answered them briefly, and then deflected their interest by asking some of my own.

‘And what about both of you? Any husbands?’ This prompted one of the most enlightening discussions I've ever had in India.

‘Oh no, we don't want to get married,’ they chorused. ‘Once we get married, we'll have to give up working and look after our husband's family.’

‘Really?’ I said in surprise.

‘Yes, in India, traditionally when a girl gets married she goes to live with her husband and his parents. Everyone lives together in the same house. A wife must take care of her husband's family while the husband earns t

he money to support them. We're not ready to spend our lives cooking and cleaning for other people all day. We like our work here.’

I was amazed. Coming from a country with a culture that cultivates independence, the idea of not only having to live with the in-laws but also to look after them was completely incomprehensible to me. Travelling around India as a tourist, I hadn't had the opportunity to find out much about daily life in India, and was keen to know more.

‘So, how old are you both, and where do you live? And do you have any boyfriends?’

‘We're 24 and 26,’ they replied. ‘And we live with our parents.’

It was no surprise to learn that they were still living at home, but all the same it was a little perplexing. Like most young people in Australia, I'd been so anxious to move into my own place as soon as I'd finished university and started work. I couldn't wait to taste freedom. But that kind of freedom, while not only a rarity, was also quite unacceptable in traditional Indian society.

‘Boyfriends? No!’ they giggled, embarrassed. ‘Our parents will arrange our marriage for us.’

And how would they find prospective grooms?

‘Our parents will talk to people or advertise,’ the women explained. ‘Then they will come to the house and we'll meet them. Of course, we can say if we don't like them but it's not the case for everyone. The most important thing is that both families agree. In India, it's not just the couple who becomes joined, it's the families too.

‘See, for us Indians, love and affection grow after marriage. Husbands and wives learn to love and respect each other. It's not like in the west, where people initially try so hard to impress each other, have so many expectations, then fall out of love and get divorced. In India, marriage is about partnership and compatibility. A lot of effort is put into finding a compatible match with a good family of similar background and financial status. This helps ensure that the couple stays together.’

Given my situation, I could definitely see the merit in arranged marriages, difficult as the idea is for westerners to fathom. In India, marriage is more about duty, whereas in the west it's about finding ‘The One’. Many westerners view the idea of having to marry someone who they hardly know, or aren't even attracted to, as almost barbaric. In India, the arranged marriage produces the best and most stable outcome because other factors, apart from emotions, are taken into consideration.

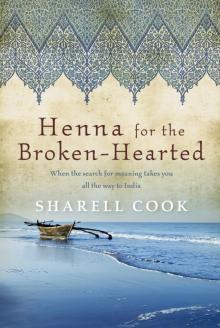

Henna for the Broken Hearted

Henna for the Broken Hearted